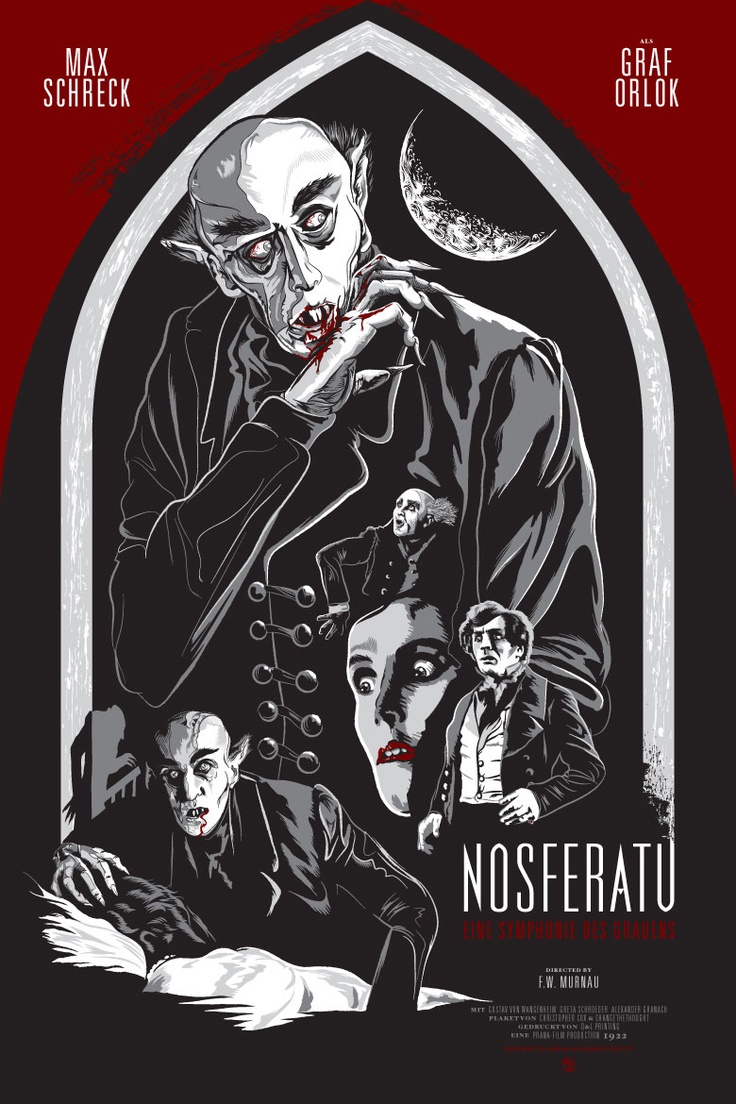

Along with interviews featuring some of the horror genre’s most fascinating women, CineDump is also proud to showcase reviews, discussions, and ramblings celebrating some great horror movie heroines and villainesses. For our first entry, we’ll look back at one of the earliest horror movies made, 1922’s Nosferatu.

Coming just three short years after the groundbreaking The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919), Nosferatu employed some at the time cutting edge technology, surreal imagery, and a familiar (but not too familiar) story to capture the fears of its audience. Like its predecessors, Nosferatu draws from German Expressionists to achieve its signature brooding style, but unlike the notable horror films that came before, Nosferatu takes a radically different approach to its heroine.

For those unfamiliar with the plot, it’s almost straight Bram Stoker’s Dracula--but don’t let director F.W. Murnau hear you say that. Stoker’s widow took him to court over cribbing her late husband’s novel, but Murnau claimed the story was significantly different enough to be his own creation. The basic arc is simple: A naive young businessman leaves his adoring wife/fiancee to close a deal with a shady foreigner. While at the stranger’s foreboding castle, he encounters some seriously disturbing things before realizing the truth about his new host’s eating habits. Our hero is powerless to stop the creature from making off for home, and before he can intervene, the monster has set his unholy sights on the protagonist’s wife. To stop the vampire’s reign of terror, it’ll take some decisive action and quick thinking.

Swap out some names here and there, and Nosferatu and Dracula are practically twins--except for one important plot point. While Hutter is in every way Stoker’s Harker, and the nefarious Count Orlock is essentially a copy of Dracula, Murnau’s Ellen differs just enough from the novel’s Mina to be revolutionary. For the majority of the film, though, you wouldn’t know it. Ellen, like her predecessor, is a perfect Victorian doll--pretty, sweet, quiet, loving to a fault. She stays at home and is happily left in the care of her husband’s friend. She faints, she suffers from “blood congestion;” no one believes her when she receives a vision of her imperiled husband--she’s just a hysteric, after all. But Ellen bears all this quietly. However, when Orlock comes to town, bringing madness and contagion with him, she makes a striking departure from Stoker’s heroine.

When Hutter comes home, he’s got a book that explains vampirism and, more importantly, how to defeat it. He forbids his darling wife from reading the book, but Ellen doesn’t listen. She learns that the vampire will die if exposed to sunlight, but bloodsuckers know to avoid even the first rays of dawn. So, to trick a vampire like the lustful Orlock into staying out after curfew, a beautiful woman, pure of heart, has to beguile him with her blood. As soon as Ellen reads this, she understands what she must do, and ultimately, it is her sacrifice, and not the impotent machinations of the male characters, that saves the world from Orlock’s evil.

Looking at this story from a purely modern perspective, Ellen seems less than an empowering heroine. She spends the majority of the film being treated like a precocious child and what’s worse, submitting to this patronizing treatment without complaint. Before decisive scenes, she faints, furthering the stereotype of the hysterical woman. However, Ellen is the story’s hero, the only one who can face the reality of what must be done to stop Orlock. Sure, she’s not an unapologetic ass-kicker like Sharni Vinson’s character in You’re Next, nor is she actively trying to smash the patriarchy, but she’s still the hero.

Think about the two major horror films that preceded Nosferatu: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and The Golem. Both of these “Grandfathers of Horror” feature weak female characters that constantly need to be saved. The somnambulist Cesar of Caligari carries off sleeping beauties for his fascist master, and The Golem features a fatuous temptress who causes more problems than she solves. In Nosferatu, Ellen is constantly underestimated but despite this, she takes on a mythic status as Christ-figure, offering herself to blot out disease and sin. Yes, her martyrdom is particularly gendered--laying in bed, using her beauty and purity to trick the dark foreigner, but, the fact remains, she’s the first representation in horror of a woman taking control of her own destiny--and saving others in the process.

Murnau radically altered the end of Stoker’s book which sees a posse of enlightened white men team up to outwit Dracula. Mina is entirely under his sway and without a gang of privileged male stereotypes to save her, she would have spent eternity as one of Dracula’s carnivorous brides. Nosferatu’s Ellen stands up to the monster and slays it. She uses her cunning and her sexuality and her bravery to do what a long line of men failed to do. Without this first portrayal of a heroic woman, none of cinema’s stronger leading ladies would have had a chance to be born. It may seem like a small step now, but, in 1922, it was a step in the right direction. So, here’s to the first lady of horror heroines, Ellen Hutter.

Pennie Sublime