In Shaman, director Antonio Negret ventures into the jungle of spiritual warfare, cultural conflict, and unsettling ambiguity to deliver a horror film that’s both deeply atmospheric and thematically resonant. With a haunting score, visually rich cinematography, and a genuinely unnerving sense of dread, Shaman manages to inject new life into the well-worn exorcism subgenre—even if it doesn’t fully commit to its most provocative ideas.

The film follows a missionary family in rural Ecuador whose young son (Jett Klyne) returns from a forbidden cave seemingly possessed by an ancient, malevolent force. His mother, Candice (Sara Canning), insists on a traditional Catholic exorcism, while her husband Joel (Daniel Gillies) remains skeptical. Meanwhile, the local shamans—sidelined by the missionaries’ presence—recognize the spirit as something far older and more dangerous than what Western religion can handle.

This theological and cultural tug-of-war is Shaman’s most fascinating element. At its best, the film critiques the white savior complex and the often hypocritical nature of religious colonialism. These ideas are embodied visually, as in one striking image of a glowing, almost ethereal missionary woman offering salvation like some divine ghost of Manifest Destiny. But just when the film flirts with fully leaning into this critique, it sidesteps the statement, favoring a more traditional possession horror arc in its third act.

Still, the execution is impressive. The performances—particularly from Canning and young Jett Klyne—elevate the material. Klyne is astonishingly good, channeling an Exorcist-level intensity that’s far removed from his earlier Marvel work. Canning does remarkable work with her eyes alone, often conveying desperation, doubt, and dread in the same breath. Daniel Gillies delivers a solid performance as the skeptical husband, though the inconsistent beard length throughout the film becomes an unintended distraction.

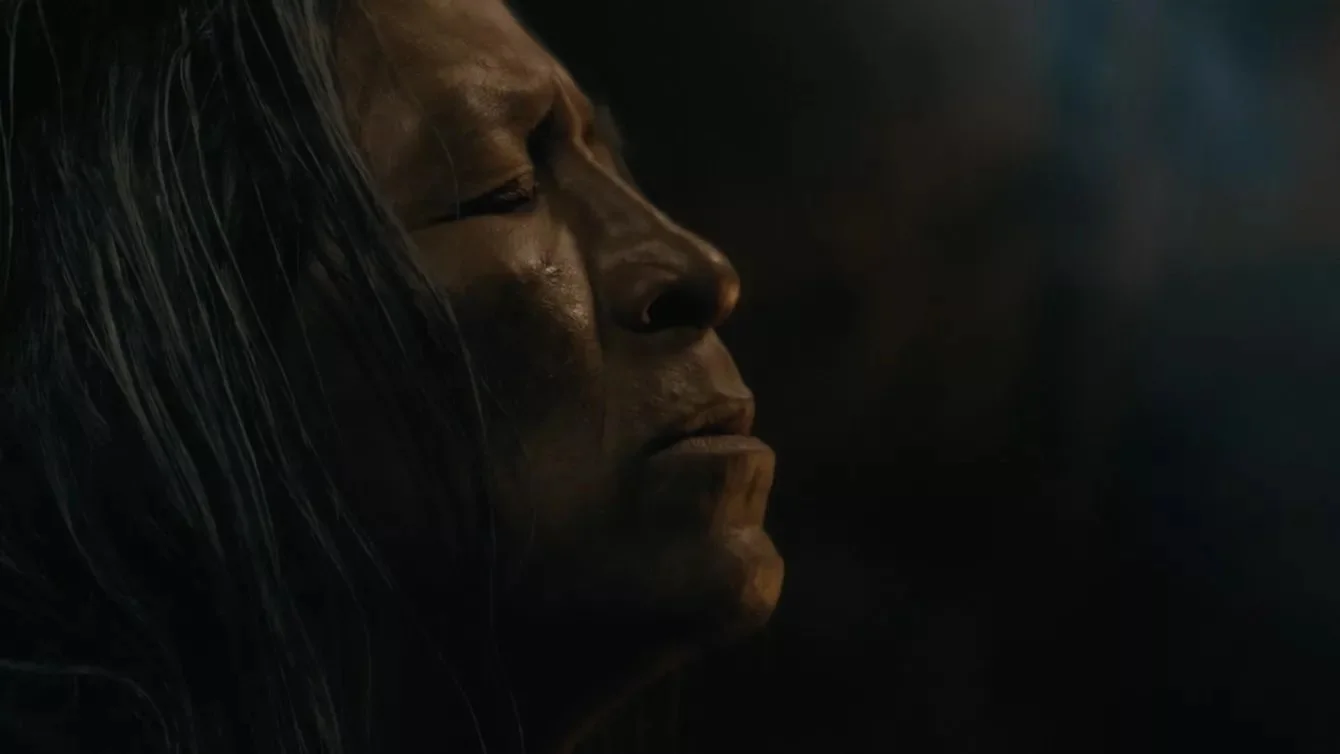

Visually, the film is stunning. The Ecuadorian jungle setting is not just a backdrop, but a character in its own right—lush, mysterious, and ever-threatening. The makeup effects are stellar; the dead look truly dead, and the wounded genuinely in pain. Even the CG scorpions—used perhaps a bit too liberally—are serviceable and contribute to the surreal, creeping unease. And then there’s the score: a dissonant, unnerving companion to the visuals that enhances the film’s oppressive atmosphere.

There is a sex scene between Candice and Joel that feels jarringly out of place—tonally disconnected from the rest of the film and its more serious themes. But it’s a rare misstep in a movie that otherwise keeps you engaged and uncomfortable in equal measure.

What ultimately makes Shaman worth watching is its unique perspective. Unlike many exorcism films that mimic The Exorcist beat-for-beat, this one approaches possession through the lens of indigenous belief systems versus imposed Western faith. It’s a smart, often horrifying look at how cultural imperialism repackages evil, sometimes in the name of salvation.

The ending ties things together in a clever and horrific way, leaving a knot in your stomach. While Shaman doesn’t take every risk it could have, it’s still a bold and thought-provoking entry into modern horror—one that dares to say something different, even if it sometimes whispers when it should scream.

Jessie Hobson