Bryan Fuller’s Dust Bunny feels like the kind of film a future filmmaker will treasure as a kid, the sort of movie that plants the idea that cinema can look and feel like anything. It is whimsical, eerie, funny, beautiful to look at, and anchored by a sincerity that sneaks up on you. Fuller brings the sensibilities of Pushing Daisies and Hannibal into a fairy tale about fear, imagination, and the emotional truth of childhood. It is a lot to juggle, yet the film rarely loses its balance.

The story follows ten-year-old Aurora, played with remarkable presence by newcomer Sophie Sloan. Aurora believes the monster under her bed has eaten her family. Her solution is to hire the mysterious hitman next door, played by Mads Mikkelsen, to kill it. Fuller frames nearly every beat through Aurora’s perspective, which creates a heightened, dreamlike world that mixes fantasy horror with hitman action and moments of childlike wonder. Wallpaper ripples like water, floorboards rise and fall in seamless effects work, and shadows slither with intention. It is an approach that calls back to early Del Toro, Jim Henson, Jeunet and Caro, and even Studio Ghibli, but Fuller shapes it into something distinctly his own.

Sloan is extraordinary. You feel her fear and uncertainty in every close-up. Her emotions register clearly without ever tipping into precocious movie-kid territory. When she is frightened, the world bends with her. When she is bold, it expands. The film depends on her honesty, and she carries it with ease. Mikkelsen, of course, is effortlessly compelling. He plays the Neighbor with weary grace and sharp comedic timing, and his chemistry with Sloan gives the movie its heart. Their odd little partnership becomes the emotional anchor in a film stuffed with assassins, creatures, and chaotic set pieces.

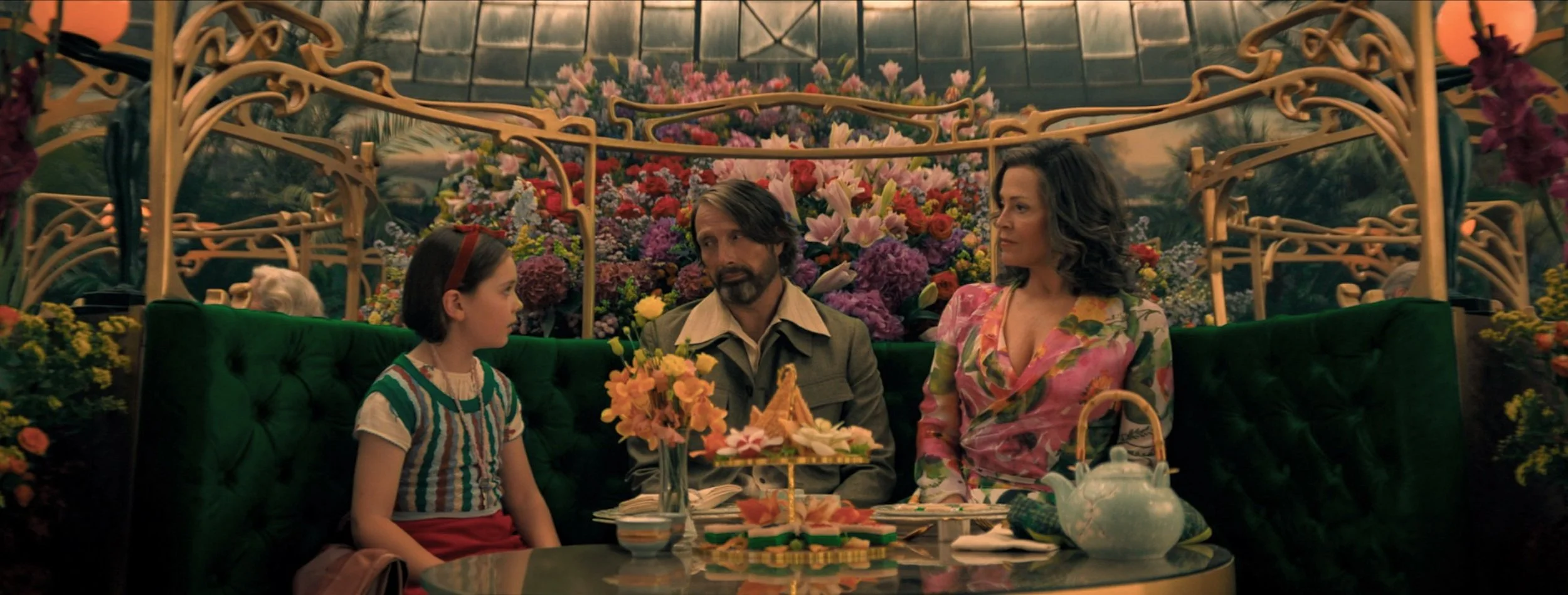

The production design deserves its own applause. Fuller and his team treat every location as a visual feast. Aurora’s room is a pink collage of childhood innocence tinged with quiet menace. The dim sum sequence, set against an aquarium window where sharks circle behind Mikkelsen and Sloan, is as striking as anything Fuller has put on screen. The greenhouse tea room looks like a dream painted in florals and pastel architecture. Every blanket, tapestry, and wallpaper pattern feels deliberate. The blocking is precise and painterly. Nothing is wasted space.

Fuller’s choice to shoot the world as Aurora sees it gives the film a unique charm. Sometimes it feels like a Stephen Chow comedy. Other times it resembles a live action Roald Dahl fever dream. The tone moves between action, fairy tale, and childhood terror with surprising control. The score matches the visuals perfectly, and needle drops like Sister Janet Mead’s “The Lord’s Prayer” or ABBA’s “Tiger” add their own strange spark.

The creature itself is both impressive and disarmingly cute, which Fuller uses for emotional effect. Practical work blends with CGI in a way that feels tactile and warm, even when the monster is tearing up a room. A few digital choices stand out more than they should, yet the design remains charming enough that it never disrupts the film’s tone.

If there is a limitation here, it is that the movie occasionally overcommits to its quirks. A few beats, including an eye-rolling final moment with Sigourney Weaver, land with less grace than the rest of the film. Some viewers may wish the story pushed further into the consequences of Aurora’s fear instead of dancing around them. But even when the film stumbles, it does so with personality.

Dust Bunny succeeds most as a celebration of imagination and the sometimes frightening inner world of children. Fuller avoids the temptation to moralize. Instead, he takes Aurora’s fears seriously and invites the audience to do the same. It results in a film that is clever, stylized, heartfelt, and visually intoxicating. It is also genuinely funny and surprisingly wholesome for a movie about a hitman and a monster under a bed.

They truly do not make movies like this anymore. Dust Bunny is equal parts fairy tale, action movie, and childhood nightmare. It is Guillermo del Toro for teens, a little Little Nemo, a little James and the Giant Peach, a little Where the Wild Things Are. Most importantly, it is a unique gem that feels like it came from a filmmaker who knows exactly what he wants to say and exactly how he wants it to look.

Jessie Hobson