Traumatika opens with a statement about the five forms of childhood trauma, setting the stage for what could have been an unsettling and focused horror exploration of generational abuse. Directed, produced, and edited by Pierre Tsigaridis (Two Witches), the film is part possession horror, part slasher, part talk-show melodrama, and that genre mash-up is both its strength and its downfall.

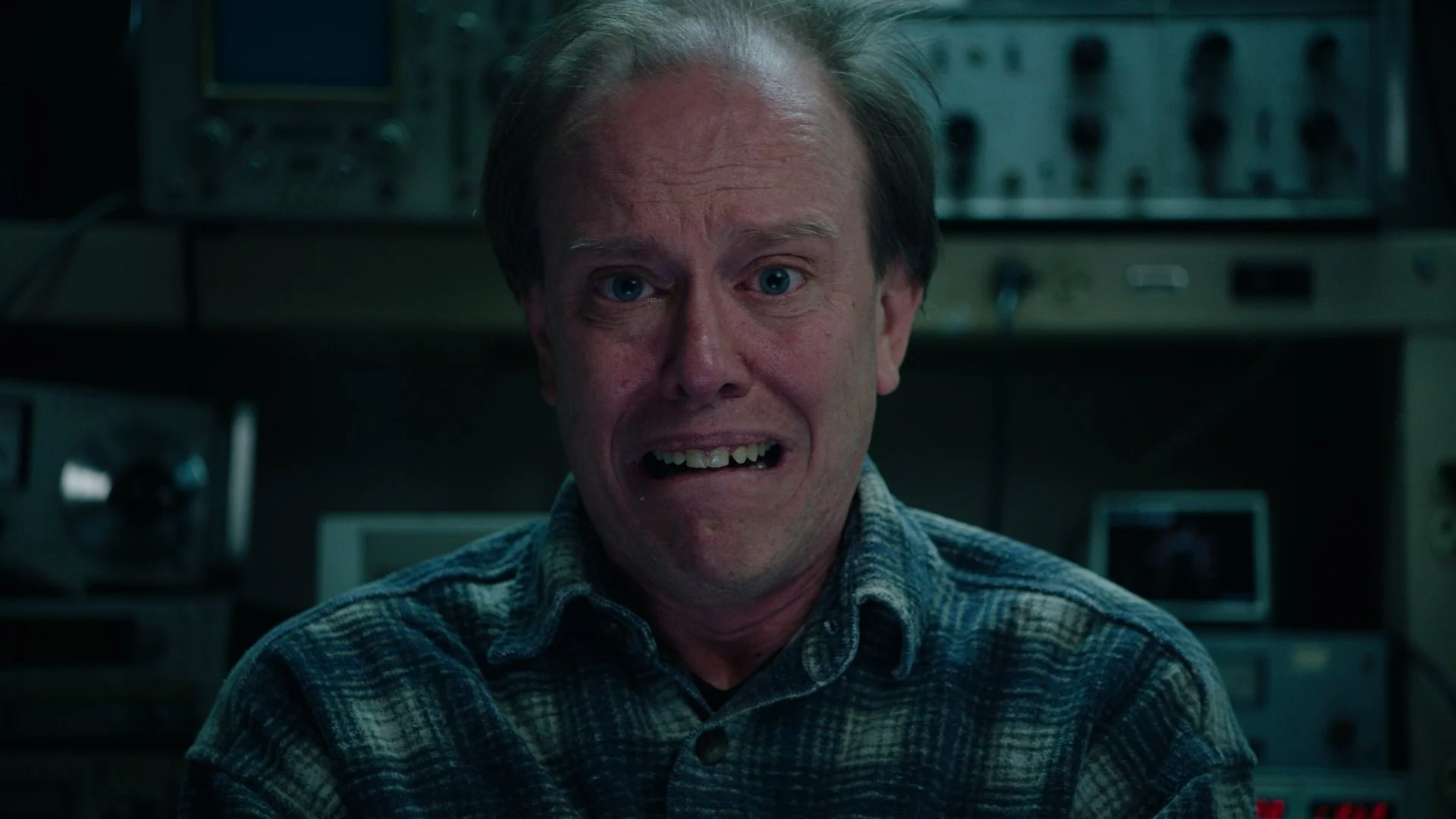

The marketing push leaned into notoriety, with its trailer banned from YouTube, sparking curiosity about what could possibly be too extreme for the platform. Early scenes certainly deliver on shock value: Rebekah Kennedy’s performance as Abigail, a woman possessed and deeply broken, is genuinely haunting. Whether crawling at her victim on all fours or simply sitting in eerie stillness, she balances over-the-top theatrics with moments of quiet menace. Sean O’Bryan also makes an impression as John, a father whose possession manifests in vile and deeply uncomfortable ways, including a scene so disturbing it’s hard to watch.

At its best, Traumatika combines grotesque imagery such as bathtubs full of blood, monstrous POV chases, and some truly unsettling creature design with a willingness to confront the ugliest aspects of abuse. The monster itself, a charred, Descent-like creature, works best in quick glimpses, and some of the film’s handheld, almost Cloverfield-style sequences generate real tension.

Unfortunately, the film also feels like it’s working against itself. The narrative is told in a chaotic jumble of time jumps: Egypt in 1911, then 2003, back a year, forward twenty years, then Halloween, which makes it unnecessarily disorienting. While nonlinear storytelling can enhance a film’s mystery, here it often feels like a distraction. Even more jarring is the tonal whiplash. Traumatika veers from stomach-churning depictions of assault and trauma to goofy slasher one-liners and bizarre comedic beats, like a possessed killer randomly doing a vaudeville-style dance or putting on a trucker hat moments after a murder.

The final act pushes into absurd territory, blending talk show segments, slasher mayhem, and demon mythology, but by then, the emotional core has been buried under tonal inconsistency. The ending aims for a tongue-in-cheek “badass” moment, but instead lands awkwardly, undercutting what could have been a harrowing conclusion.

Still, there’s no denying the ambition here. Tsigaridis is not afraid to take risks, and when Traumatika leans into its psychological and social horror, examining how abuse echoes through generations, it is genuinely powerful. The performances are committed across the board, and certain sequences will brand themselves into your memory.

Ultimately, Traumatika is a messy but memorable ride, one part nightmare, one part exploitation, and one part midnight-movie absurdity. There is a good film buried inside this chaos, but it is hard to find under all the time-hopping and tonal detours. Whether you are disturbed or laughing, sometimes at the wrong moments, you will not forget it anytime soon.

Jessie Hobson