There’s a particular kind of passion that only reveals itself when a filmmaker stops talking about plot and starts talking about why something scares them. That’s where Jeremiah Kipp lives.

Before sitting down to talk with Kipp, I wasn’t familiar with The Mortuary Assistant video game, nor was I deeply acquainted with his body of work beyond reputation. By the end of our conversation, I was not only sold on his film adaptation but actively curious to dig backward through his filmography and forward into the game that inspired it. That curiosity didn’t come from hype or branding. It came from how deeply Kipp understands fear as something emotional, psychological, and uncomfortably personal.

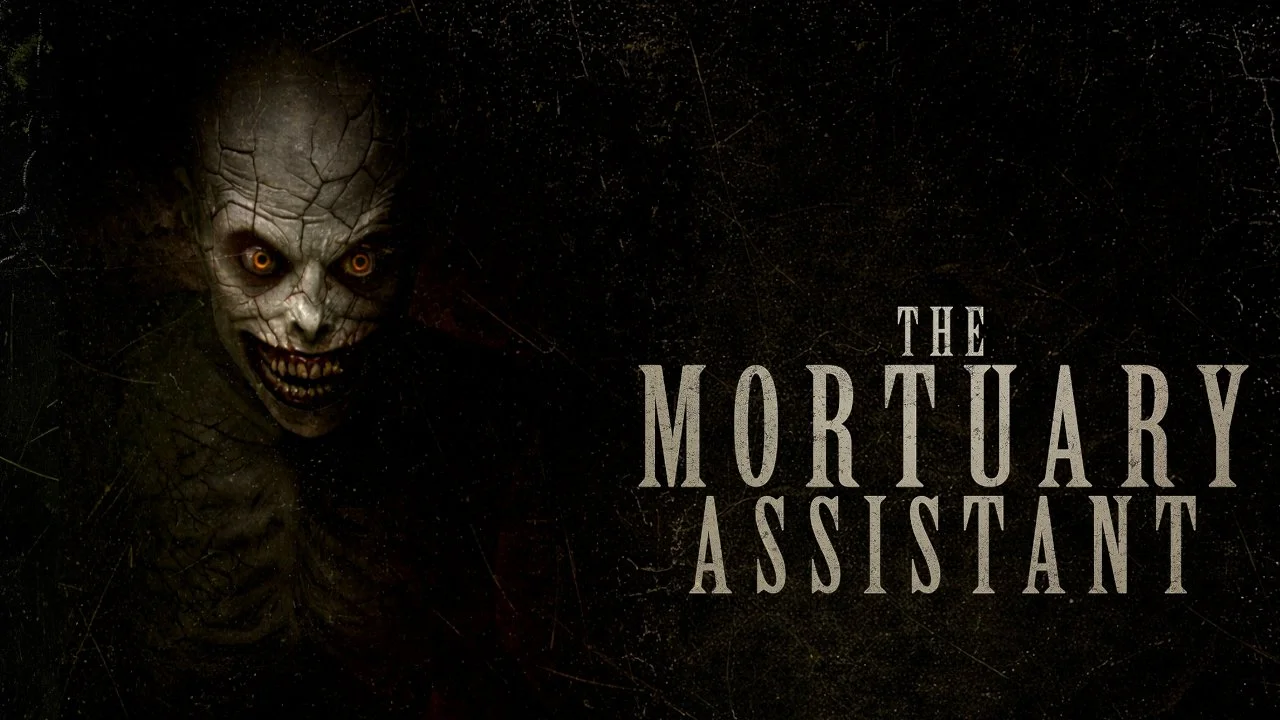

Kipp, best known for the Shudder Original Slapface, approached The Mortuary Assistant with no interest in recreating a “playable scare system” beat-for-beat. Instead, he locked onto character first. “The kind of horror movies that I like to make are character-driven,” Kipp explained, citing The Silence of the Lambs as a guiding influence and pointing to how Jonathan Demme rooted terror in Clarice Starling’s perspective.

That same philosophy shaped how he approached Rebecca Owens, the film’s protagonist, played by Willa Holland. “I pinned the entire movie on Rebecca Owens,” Kipp said. “If I can make the audience care about her and want to be with her on her journey, then when things happen to her, the audience is going to have an investment in it”.

That investment matters because The Mortuary Assistant is a film about routine, isolation, and the lie of safety. Rebecca embalms bodies alone at night, and the film takes its time letting that work feel normal. Kipp wanted the audience to settle into the rhythm before pulling the floor out from under them. “Waiting for something terrible to happen is one of the worst experiences you could possibly have,” he said. “That state of anticipation and dread is closer to the game and closer to the things I find truly terrifying”.

Even without prior knowledge of the game, the film’s visual language communicates that unease clearly. There are shots framed from low angles and partial POVs that subtly echo survival horror games without turning the film into a gimmick. When I mentioned that those moments reminded me of classic genre filmmakers like Bob Clark, Kipp lit up. “That’s music to my ears,” he said. “He always put you in the perspective of the character in danger”.

The environment itself does much of the heavy lifting. River Fields Mortuary feels oppressive, real, and lived-in. That realism extends to the film’s most stomach-turning moments: the embalming scenes. These sequences lean hard into practical effects, establishing early on that the film “means business.” Kipp compared the approach to George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, using shock early so the audience can acclimate and lower their guard. “Once you realize this is Rebecca’s job, there’s nothing to fear from the dead,” he said. “The dead are not the problem”.

What is the problem, according to Kipp, lives inside the mind. He describes the film’s demonic forces less as monsters and more as manifestations of depression, intrusive thoughts, and emotional self-destruction. “The monsters in our movie attack you in your mind first,” he explained. “They break you down, and then they go in for the kill”.

That psychological focus is reinforced by the film’s muted color palette. Dominated by grays and cold blues, the look was established early in conversations with the cinematography, production design, and effects teams. Kipp described it as having a “bleach bypass quality,” something closer to the texture of corpses themselves. “There’s a beauty to that kind of color palette,” he said. “It puts us in a melancholy space where we know strangeness is coming”.

Willa Holland’s performance is the emotional anchor holding all of this together. Kipp was drawn to her restraint, noting that “by her pulling back, the audience leans closer.” When Rebecca’s possession begins, Holland doesn’t exaggerate the shift. Instead, Kipp encouraged her to tap into the most self-critical voices inside herself. “Those voices latch on to you,” he said. “She didn’t ham it up. Even playing a demon, she kept it grounded and realistic”.

That grounding extends even to moments of tonal irony, like the lo-fi music Rebecca listens to while working. It’s both an Easter egg for fans of the game and a reflection of real mortuary practice. “A lot of morticians play music while they’re working,” Kipp noted. “There’s something playful about having that kind of music playing while you’re doing something people see as morbid”.

Despite the growing attention around video game adaptations, Kipp never treated The Mortuary Assistant as a trend-chasing exercise. “I didn’t want to make a video game into a movie,” he said. “I wanted to make this video game into a movie because I cared about the world and the story and the characters so much”.

That care is evident throughout the film and throughout the conversation. By the time our interview wrapped, it was clear that Kipp isn’t interested in theme park horror. He wants audiences to meet the film emotionally. “It’s an emotional journey with a character,” he said. “I hope they receive the film in the spirit from which it was made, with love, care, and sympathy. And I hope they also get a good fright out of it”.

After speaking with him, I did too.

Jessie Hobson