There’s a particular kind of unease that settles in while watching Dooba Dooba, the creeping sense that you’re witnessing something private, intrusive, and deeply wrong. That discomfort isn’t accidental. It is the result of deliberate, fearless choices by writer and director Ehrland Hollingsworth and lead actor Amna Vegha, two collaborators who clearly understand the power of restraint, implication, and risk.

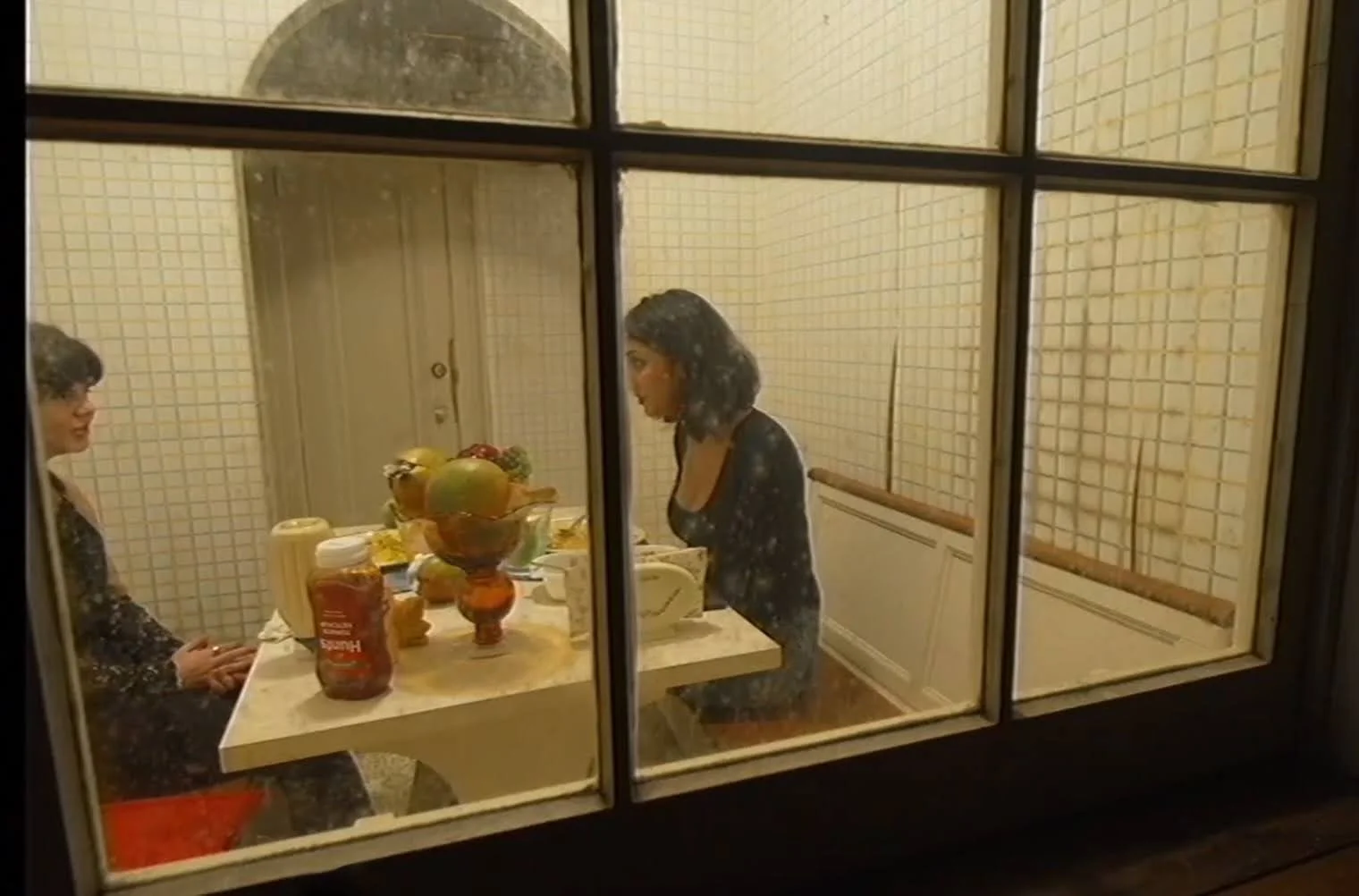

Shot almost entirely through in-home security cameras, Dooba Dooba reframes the found footage format into something colder and more voyeuristic. Hollingsworth explains that this sense of intrusion was baked into the film from its earliest conception. “Every time you watch security camera footage, it feels like something bad is going to happen,” he says. “And you shouldn’t be looking at it… by watching it, you’re sort of causing what is occurring, at least being involved in it.”

That complicity is what gives the film its bite. Unlike traditional handheld found footage, Dooba Dooba places the audience in a passive but morally uncomfortable position, watching from fixed angles, unable to intervene, yet unable to look away.

For Vegha, that invasive setup was paradoxically freeing. Acting without a visible crew, large cameras, or traditional coverage allowed her to fully inhabit the space. “It really just felt like we were two girls playing in this space,” she recalls. “It feels really controlled when you watch it back, but as an experience it was completely free.”

That freedom translates into a performance that feels raw, natural, and disarmingly intimate. Much of the dialogue has an awkward, lived-in quality, which some viewers might assume is improvised. Vegha is quick to clarify that the effect came more from character-specific writing than looseness on set. “He wrote my character really based off of my normal speech patterns,” she says, noting that the character even wears her own clothes. “It did just feel very natural in that way.”

Hollingsworth confirms this was intentional. “I wrote it with Amna’s voice in my head,” he explains. Vegha adds, “A lot of the emotion comes from the action itself.” The result is dialogue that doesn’t feel scripted so much as observed, another layer of the film’s unsettling realism.

Formally, Dooba Dooba is confrontational. It jumps between security footage, POV shots, erratic captions, and archival clips, often cutting scenes at their emotional peak rather than allowing release. Hollingsworth describes the editing process as a constant negotiation between chaos and control. “Once you start breaking the rules, there’s a reason those rules exist,” he says. “You have to know when to dial back, otherwise you’re just being weird for its own sake.”

That balance is what keeps the film from collapsing under its own experimentation. Scenes escalate from mundane to disturbing, then abruptly cut away, carrying unresolved tension forward. Hollingsworth cites Inglourious Basterds as a structural influence, specifically its elastic approach to suspense. “How long can you stretch that rubber band before it snaps?” he asks. “You can keep stretching it.”

Much of the film’s oppressive atmosphere comes from its setting, an unassuming house that quickly becomes a character in its own right. The location predates the script entirely. “The house came before the film,” Hollingsworth says. “Everything was designed around it.” For Vegha, the environment was transformative. “You really just feel like you’re in it,” she says, citing the isolation, the darkness, and even the smell of thrifted pillows as elements that grounded her performance.

Notably, Dooba Dooba refuses to explain itself, even as it grows increasingly disturbing. That ambiguity is a feature, not a flaw. “Explaining yourself ruins the mystery,” Hollingsworth states plainly. “It gestures at things, but it never points at them.”

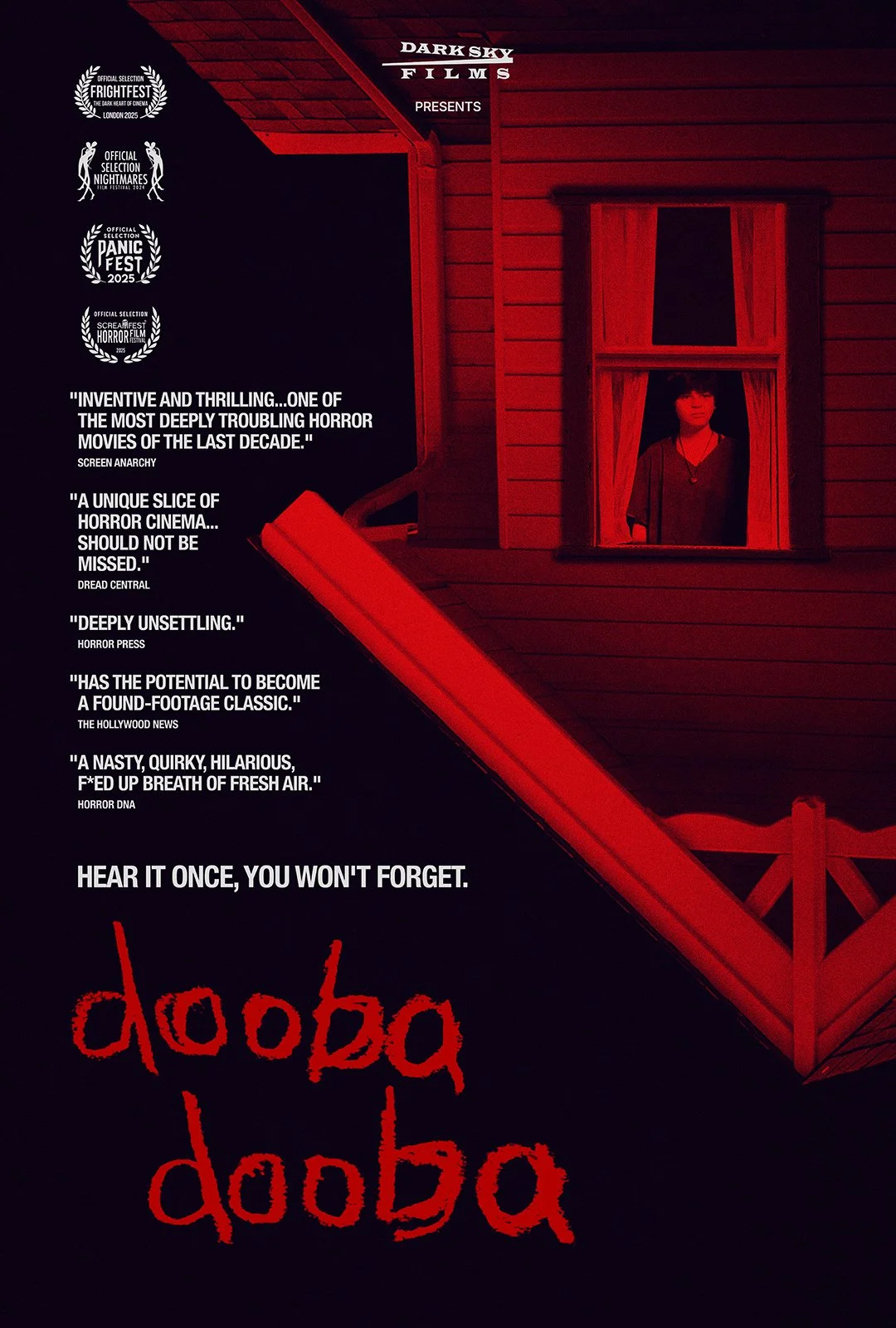

Despite its experimental nature, the film has resonated strongly on the festival circuit, earning major awards and frequent comparisons to Skinamarink. Both filmmakers seem genuinely surprised by the response. “We did this whole film so casually,” Vegha admits. “It just felt like a small group of friends having a really good time.”

That spirit carries into conversations with Hollingsworth and Vegha, both of whom are generous, thoughtful, and refreshingly candid about the risks they took. As someone increasingly drawn to found footage and analog horror, speaking with them only reinforced the sense that Dooba Dooba is something special, original, volatile, and unafraid to alienate in pursuit of something honest.

With its theatrical and digital release through Dark Sky Films, Dooba Dooba stands as a bold entry in the evolving language of horror. More than anything, it marks Hollingsworth and Vegha as collaborators worth watching closely. If this film is any indication, whatever they do next will be just as challenging and just as hard to look away from.

Jessie Hobson