There is an immediate sense, watching Dooba Dooba, that you are seeing something you are not supposed to see. Shot almost entirely through static home security cameras and lo-fi video fragments, writer-director Ehrland Hollingsworth’s unnerving babysitting nightmare doesn’t just flirt with discomfort, it lives there. This is analog horror stripped to its rawest nerve, messy, abrasive, and deeply unsettling in a way that feels intentional rather than indulgent.

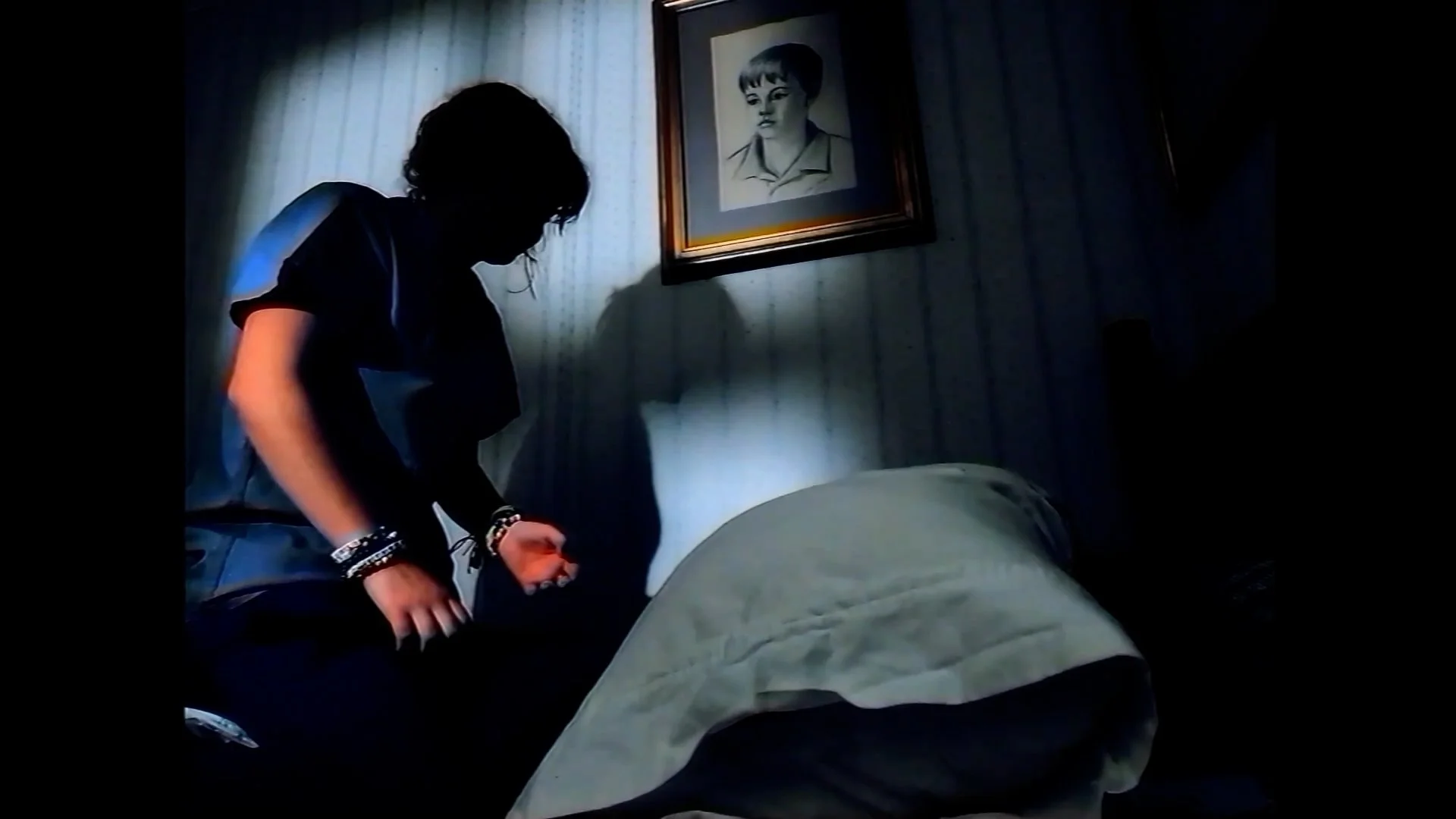

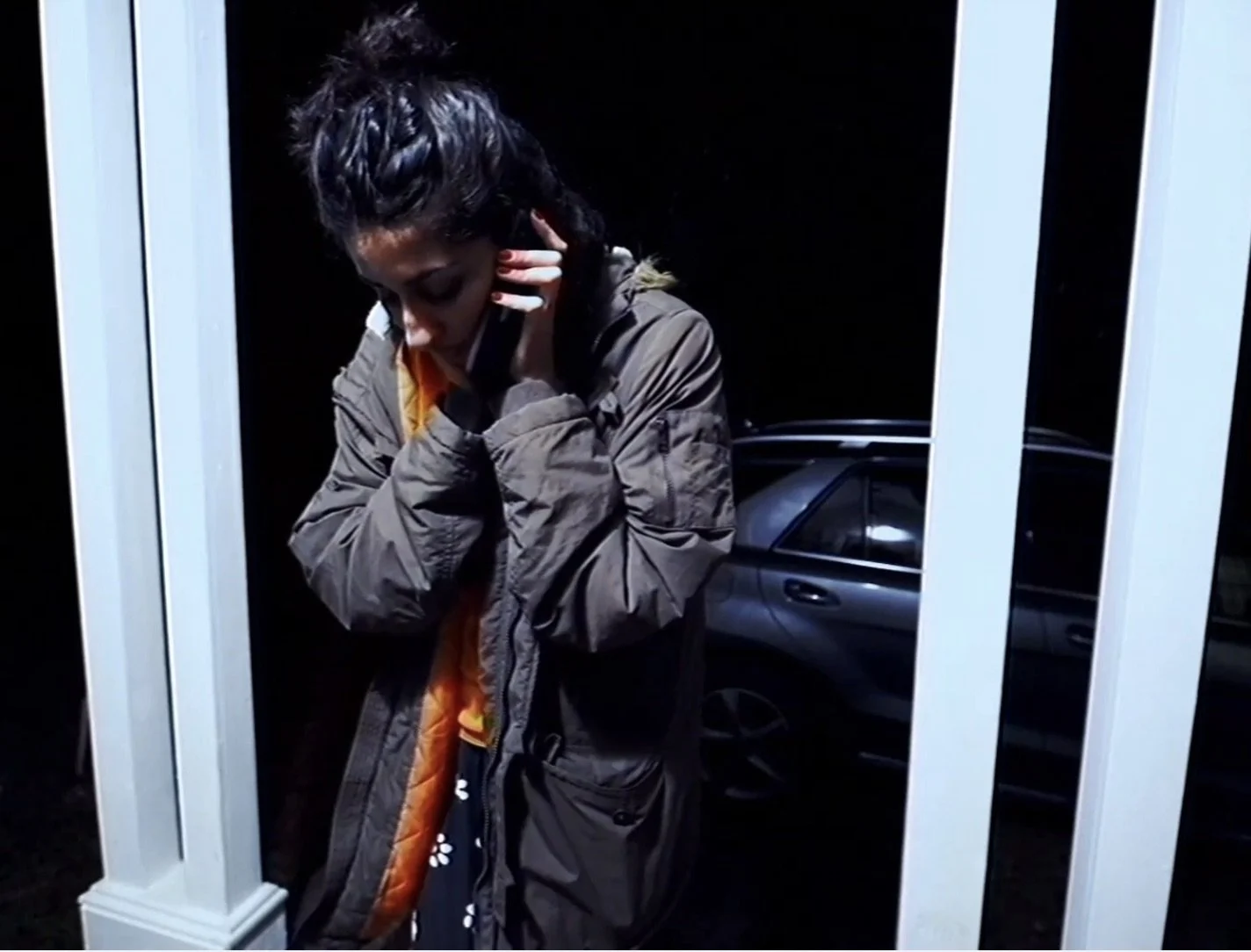

The setup sounds deceptively simple. Amna, a young woman taking a routine babysitting job, is tasked with watching Monroe, a withdrawn teenager whose trauma lingers in the house like a stain. The rules are strange from the start. Amna must announce herself by saying “dooba dooba” whenever she moves through the house, as if language itself is a safety mechanism. Cameras watch every room. Boundaries erode quickly. What follows is a slow, disturbing unraveling of power, control, and attachment that grows more claustrophobic with every scene.

What makes Dooba Dooba so effective is its refusal to behave like a normal movie. Dialogue often feels improvised, awkward, and uncomfortably real. Scenes begin innocently, sometimes even mundanely, before boiling over into something deeply wrong. Early moments occasionally drag, but the odd pacing becomes part of the experience, reinforcing the sense that time itself feels off inside this house. Each scene escalates the unease, somehow topping the previous one until the film reaches moments that are genuinely hard to shake.

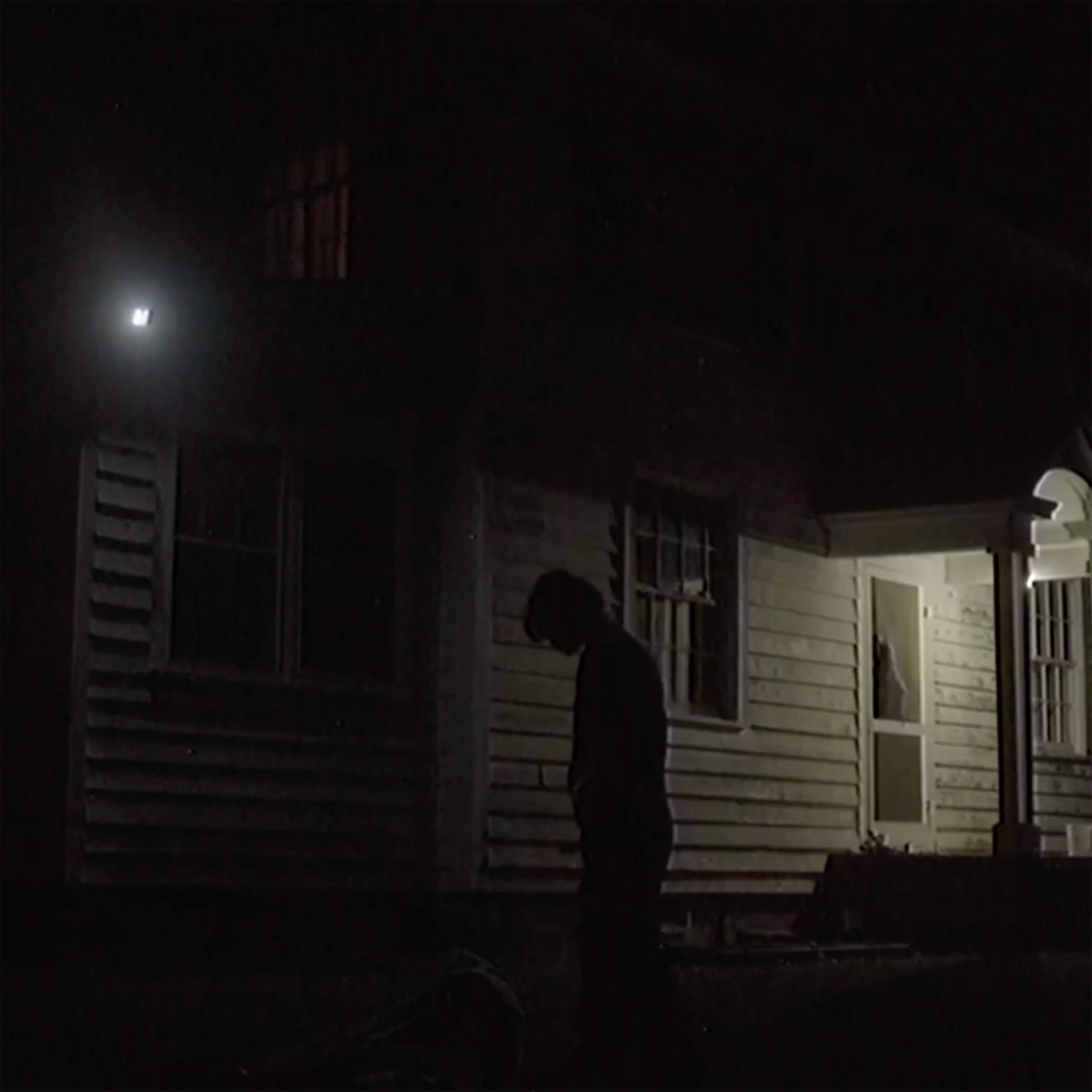

Visually, the film leans hard into its shot-on-video aesthetic, evoking the uneasiness of 90s home recordings. The house itself is painfully familiar, an unmistakable middle-American home complete with bland minimalism and ugly curtains. That familiarity makes everything worse. This could be any house. It could be yours. The film frequently jumps between found footage, point-of-view shots, erratic captions, PSA-style interruptions, and strange archival clips. These transitions are jarring and disorienting, but they are also purposeful. The movie feels like a manipulated after-the-fact video project, forcing you to question who is editing this footage and why.

There is a chaotic, almost punk rock energy running through the film. Dooba Dooba rips apart filmmaking conventions and tosses them back together without apology. It feels reckless and alive, like it could spiral out of control at any moment. At times, it recalls the dread of House of the Devil filtered through the fractured, experimental unease of Skinamarink, with flashes of Adult Swim absurdity and Tim and Eric–style awkwardness, though sharper and more sinister.

Not everything lands perfectly. As the film progresses, the momentum occasionally falters, and there are stretches that feel slightly aimless compared to the razor-sharp tension established earlier. Some viewers may find the lack of clear answers frustrating. But Dooba Dooba is at its strongest when it resists explaining itself, letting implication and discomfort do the heavy lifting.

Ultimately, Dooba Dooba is immersive, disturbing, and deeply effective as a late-night watch. It intrudes into your space, crawls under your skin, and refuses to let you fully relax. It breaks the rules of found footage and analog horror, but somehow still works because of that defiance. This is bold, volatile filmmaking that feels dangerous in the best way, and even when it stumbles, it leaves you eager to see where Hollingsworth goes next. It may very well become the Skinamarink of 2026, an experimental horror outlier that divides audiences while haunting the ones who let it in.

Jessie Hobson